#NotJust An Exam

Reflections on the Himalayan Challenge of Evaluating Ethics through An(y) Examination

Hello Dear,

In the previous One Doubt Please post, we discussed why the real decisions in life are decisions of morality and ethics.

When I think of it now, I realize that even many of those decisions which appear to have no ethical or moral implications often do involve questions of right and wrong, good and bad. Or is it always so, in every case, at least to some extent?

Is every decision in life an ethical or moral decision as well?

Perhaps not! I don’t quite know!

Either way, today’s post is along the same lines, on the very difficult and non-trivial challenge of assessing someone’s ethical strength and moral fibre, in the context of a selection process.

Before we delve into it, if you find some value in these reflections, do consider subscribing to this #NotJust newsletter for free, by entering your email ID below.

Let me begin by sharing with you the precise trigger for this precise strain of reflections going on in my mind as I write this. You may perhaps have heard of an Indian civil servant and IAS officer who has captured a lot of media and public attention during the last few days, for all the wrong reasons. There have been allegations of various kinds of malpractices. And the government initiated an inquiry into the matter and has initiated action as well.

Enter The Ethics Examination

Now, in the course of this discussion, I found some remarks on social media, on the merit of including the subject of Ethics in the Civil Services Examination conducted by the Union Public Service Examination (UPSC). To give a brief background, the Ethics paper was included in the examination, beginning from the Civil Services Examination conducted in the year 2013. We have thus had 11 examinations so far, where civil service aspirants were supposed to have been tested on their ethical quotient, so to say, by the UPSC.

Interestingly for me, the Ethics Paper was introduced two years after I appeared in the examination for the second time, which led eventually to my selection into the Indian Information Service. Ya, so I was saved the ordeal, so to say. 😊

So, what did I find on social media about the Ethics Paper, which provides me the fuel and fodder for writing this article? People have remarked that the case of the civil servant in question proves that…

“…Passing the Ethics paper does not instill ethics in the candidates.”

I think some people have even gone on to mock the Ethics paper. What do you think? Does passing an ethics examination instill ethics in people? I think most of us are inclined to answer “no”, to this simple and straightforward question. Is our basic intuition right? If yes, do we know exactly why we are right? Or could we be mistaken? Or “does the truth lie in between”? If so, where?

Before we explore these questions, I would like to share with you something which has once again struck me while thinking of this issue. The more we learn, the more we realize how little we know. The more we realize how much more there is to learn, even and especially about topics and issues which we thought were too trivial and simple to demand our patient attention.

As Voltaire said:

“The more I read, the more I acquire, the more certain I am that I know nothing.”

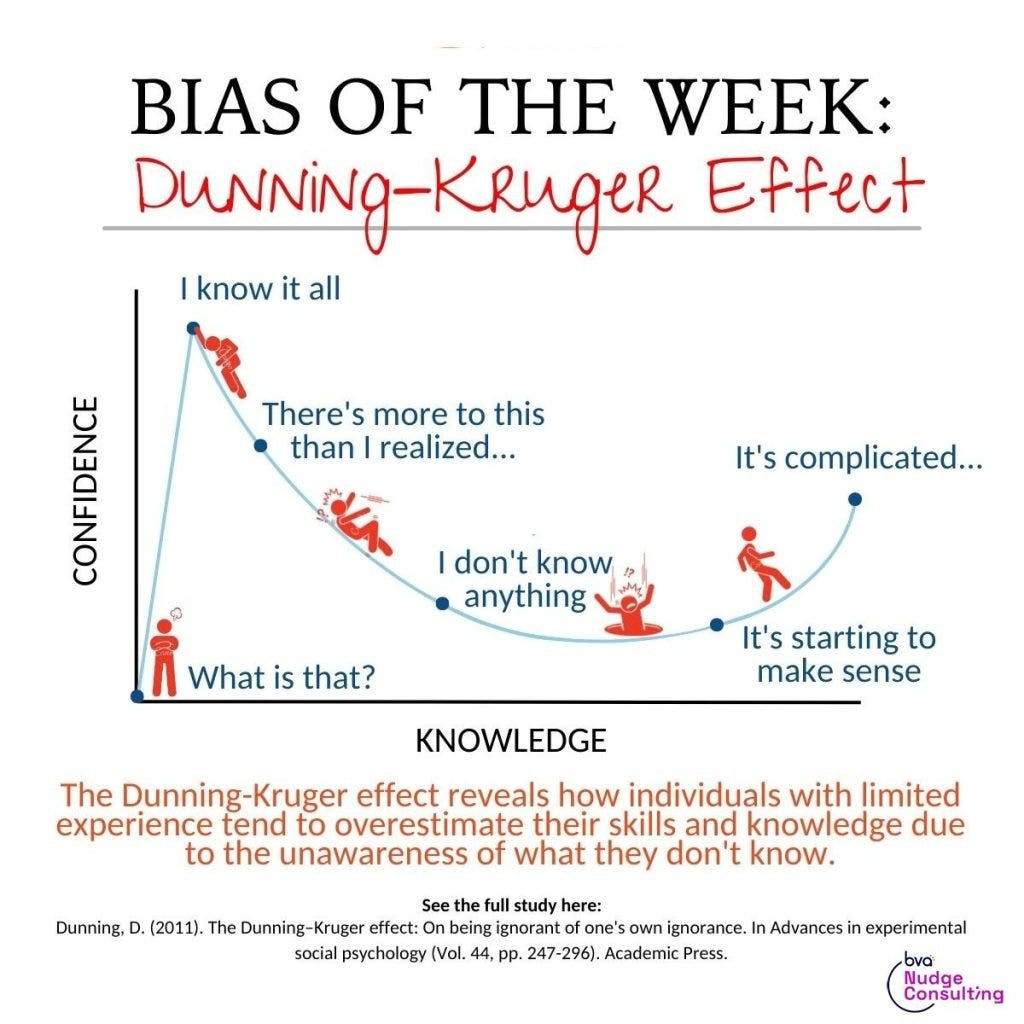

A related phenomenon is what is known as the Dunning Kruger Effect when our half-baked knowledge or skill leads us to overestimate our own capabilities, to be blinded by overconfidence.

Voila! I realize that this Effect might just be especially relevant to our discussion on the Ethics Paper. So, let us get to it. In this article, we will only examine why it is a Himalayan challenge for an Ethics Paper to serve the purpose an Ethics Paper should serve! Of course, these are based on my “limited understanding” of the issue, as at the moment. OK, here we go.

#NotJust Knowledge

So, just last week, I was trying to help a dear friend who is pursuing his Ph.D. He was presenting his research plan and methodology to me, and hence the goals of the research. My friend told me that through his research, he will be able to help a particular industry to boost their revenues and improve their profits and efficiencies.

Well, my friend is one of the most honest and humble persons I know, and he meant nothing but well. But it was my responsibility to show him how he was making an assumption which until then was not visible to him.

He expected to conduct the research and discover something, to arrive at some “research findings”. Now, he had naively hoped and unconsciously assumed that if these findings are communicated to the industry, it would, on its own, result in the industry improving its profits and performance!

A little reflection would show us that there are multiple sub-assumptions which are involved here, all of which have to be true, in order for this magic to happen. First of all, until we complete the research, we do not know what the research findings are going to be. This uncertainty is inherent to all research, isn’t it? So, the first mistake is to assume that the findings we eventually get are going to be relevant for the industry in question. Now, even if they are relevant, does it necessarily mean that they would be something which the industry players were not aware of before? No. So, this is the second assumption.

OK, so let us say that the findings are both relevant and new. Does it mean that the industry will necessarily be able to act on the findings? Absolutely no! They may or may not be. The new knowledge may enable the industry to change in certain areas, not so much in others, and may be not at all in other areas.

Fourthly, even if the industry is actually able to act on something, does it always mean that they will act on it? The answer is no, again. Especially when the knowledge is passed on to us from an “outsider”, even if it is based on inputs from we ourselves, we find it hard to accept. And indeed, there is an inherent resistance which any new knowledge which challenges our existing beliefs and practices is bound to face.

Moreover, even if someone or some people become both able and willing to change, does it mean that they will be successful in bringing it about? Not necessarily. We know that life is more complex than this, right? A lot of meaningful change involves more than one person or even group or organization. It demands them to subdue their vested interests in the service of a larger goal which they all find more meaningful and motivated by. So, systemic change - changing “the system” - is hard, not easy. Quite so, if the aim is to address legacy issues and conflicts in an industry and improve its profitability, as in my friend’s example. Hardly anything is as simple and easy as just showing someone “the way ahead”.

What is one assumption which is common to all these assumptions? The assumption that knowledge alone is sufficient to bring about change. What my friend forgot to consider is that:

Change is #NotJust about Knowledge.

Had it been all about knowledge, the world would have been a much better place, isn’t it? We could have simply focussed on creation, dissemination and diffusion of more and better knowledge among more and more people.

Of course, knowledge and education are very important. I am not, even for a moment, saying or implying that they are not. My submission is just that knowledge alone is not sufficient; it is #NotJust knowledge, in other words.😊

Wow, I am excited to share with you that I just now discovered something much deeper on this subject, by the great Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti.

Knowledge does not change man - Jiddu Krishnamurti, 1975

Learn more: Knowledge and The Transformation of Man

[I must clarify that I am yet to watch this video, as I discovered this thought of the philosopher just before writing the above lines. So, it is possible that what Krishnamurti means by the above statement is not quite the same as what we were discussing before, even though it is the same in a literal sense!]

This reminds me that another great man, Neil Postman, made a very similar point at around the same time, in 1977.

“What is distracting us from solving some of the problems you mentioned is a kind of worldview promoted especially now by computer technology…that the main reason we have problems in the world is that we have insufficient information. If only we could get more information, easier to access, and get it faster, then you could solve any of the problems you mentioned. And I think it is an awesome conceit, a terrible misjudgement. Look, if there are children starving any place, it is not because we have insufficient information. If there is crime rampant in the streets…, it is not because we have insufficient information. If the ozone layer is being depleted and the rainforest is disappearing, it is not because we have insufficient information. And if you cannot get along with your own relatives, it is not because you have insufficient information. But we have come to believe that that is the source of all misery and pain in the world, if only we had more information. And I think it is a complete distraction.” - Neil Postman, in a lecture on “The Surrender of Culture to Technology”, delivered on March 11, 1997.

So, coming back to our main question of the challenge of assessing ethical quotient and predicting ethical behaviour, we need to ask ourselves the following questions.

What is the relationship, if any, between a person’s knowledge of ethics and moral principles, and the moral and ethical standards upheld by him or her? How good is this knowledge, in predicting future ethical behaviour by the individual? How likely is it that such knowledge would lead the individual to strengthen the ethical quotient and moral consciousness of the groups and communities to which he or she belongs or may join in future?

The last question assumes relevance, especially since it is not enough that civil servants are ethical. We need them to be and become more than that.

We need civil servants to be #NotJust ethical. They should also inspire ethical and moral behaviour.

Of course, this holds for everyone of us. We are speaking of civil servants above only because our discussion revolves around the Ethics paper of the Civil Services Examination. The principles, however, are more broadly applicable, I hope. 😊

You are personally responsible for becoming more ethical than the society you grew up in. - Eliezer Yudkowsky, Artificial Intelligence researcher

What we need, in other words, is what could be described as “ethical leadership”. Here is a Harvard University article on what it is and why we need it.

Now, can testing candidates in an Ethics Examination ensure the above? I, for one, doubt that. Will it increase the likelihood that the candidates clearing the exam will behave ethically in future? In other words, does the examination do a good job in distinguishing between candidates who are likely to become ethical leaders and those who are likely to become ethically corrupt and morally bankrupt?

I need to find out what the existing research says about these questions. However, I remember reading management case studies more than 15 years ago, where I found some employers, educators and Human Resources (HR) professionals saying that ethics is not something which can be inculcated at the time of or after selection into a job. The point being that the seed has to be planted and the plant nurtured and cultivated as desired much before. According to this view, by the time people become of employable age and join companies and organizations, the quality of their ethical quotient and moral compass is already more or less well-formed - meaning that it is very difficult if at all, to change it going forward.

Well, as someone who believes in the power of change, I believe that even if it is difficult to change our ethical and moral dispositions, it is not impossible. At the same time, I think it is experience followed by conscious reflection leading to realization, a renewed sense of awareness of the world and of the self, or enlightenment in some form, which can inspire such a change. And not an exam, that too a competitive exam at that!

This discussion raises another question about the way the Ethics Paper in the Civil Services Examination fits into the larger scheme of the examination. Interestingly, there is no separate cutoff for the paper. I.e., even if one scores poorly in this paper, one could potentially make up for it to a reasonable extent and still clear the examination, even get a high rank, if one does correspondingly much better in the other papers.

So, even if one were to assume that the ethics paper does indeed measure a candidate’s ethical quotient and that it is indeed a good predictor of future ethical behaviour, a candidate can potentially flunk the paper or fail to get a high enough score and still clear the exam and get a top rank in the examination.

An alternate scenario could have been to impose a very high cutoff for the Ethics Paper. Any candidate who is not able to meet this cutoff would then automatically not pass the whole civil services examination. However, our current approach sends the message that ethics is negotiable!

OK, we have examined how a test of knowledge of ethics is not enough. Let us now talk about how the testing process poses a problem even more serious than this.

#NotJust Appearances

Remember my friend whose research project we discussed in the beginning? Let us come back to him. We discussed how he made a wrong assumption that his research findings alone will solve people’s problems, how knowledge alone would bring about change.

However, there is another mistake he made, which in turn led to the wrong assumption above. It is a mistake we are all prone to making in various spheres of our lives. And most often, I think we do it subconsciously, without our conscious awareness. Which mistake is this?

We have an inherent tendency to oversell ourselves and our ideas.

Indeed, this extends to everything that we regard as “ours” - our beliefs, our values, our actions, our achievements, our views and our worldviews. And to everyone whom we consider dear - our heroes, our dear and near ones, our friends, our well-wishers. Here is a One Doubt Please article, where we reflect on the need to combat this tendency.

Want Your Ideas to Change the World? Please Don't Forget This!

Reflections on the simple yet difficult process of transforming our ideas into impact, especially the communal and collective dimension of ideas

And indeed, the overselling extends to our weaknesses and failures too. It is just that the way we oversell them is different - rather than boasting about our weaknesses, we hide them, we keep them private or secret, we reveal them selectively. Or we sugarcoat them, we use our infinite creativity to rationalize them, or we may even present even our biggest failures as something to be proud of.

Yes, as Morgan Housel points out in his book Same as Ever:

“We do not advertise our weaknesses.”

And quite naturally, we will advertise our weaknesses even less if we are in a competition where our survival depends on those weaknesses remaining hidden and secret. On the contrary, we are even likely to reinterpret our weaknesses and present them as our strengths! If this be so,

Isn’t a hyper-competitive environment such as that of the Civil Services Examination likely to further aggravate our innate tendency to present an unduly favourable picture of ourselves?

In such a situation, I think it is easy to end up writing answers which may look impressive, are “model answers” and are “expected” to fetch good marks, even when one may not particularly believe in the answers.

Come to think of it, this is no less than a very dangerous quality.

What we need are civil servants and professionals who, inspired by the principles of truth and constitutional morality, are able to gather the ethical conviction and muster the moral courage to do the right thing, to speak and do what they believe in, even and especially when the opposite is what is “expected” or “desired”.

Even and especially when. I would like to underline that.😊Here is one of many One Doubt Please articles on this theme.

#NotJust "Following": A Case for Thinking, Reflection and Listening

Reflections on the need for thinking for ourselves, for engaging in shared reflections on our shared past, present and future

This explains why I noted earlier that what we are going to discuss is a more serious problem than that of merely placing reliance on knowledge. I am wondering…

Does(n’t) an Ethics Paper in a hyper-competitive examination such as the Civil Services Examination give a competitive advantage to precisely those candidates who are the most capable and the most willing to make ethical and moral compromises?

I do not claim that I know the answer to the above question. But I suspsect and fear whether the doubt raised could be true! After all, the rules of the game are such that those who get the highest marks are those who write what the examiners want to read. They are those who give the best answers, irrespective of whether they believe in the answers or not.

Indeed, one could argue that even those who have a strong ethical and moral signature can very well give good answers and thus score high. And they may also genuinely believe in those answers. If this be so, the system would not be discriminating against them, it would not be penalizing them for their integrity.

But then, an ethically strong candidate is also likely to be modest, right? This might hence make him or her reluctant to make claims or give arguments which convey an impression of being ethically and morally upright. A modest person would be reserved and cautious in one’s judgements. Someone who is not as modest may indulge - either consciously or subconsciously - in what is known as virtue signalling, i.e., in attempts to show that they are good, by making certain statements.

Incidentally, here are some tips given online by an IAS officer (not giving source since I do not want to name the officer), on the “strategy” for scoring well in the Ethics Paper.

Learning to use famous quotations by Mahatma Gandhi, Amartya Sen, P. Sainath and Gurcharan Das

Attempting all questions, irrespective of how little he / she knew about the topic.

Of course, one cannot necessarily find fault with the decision to attempt all questions in a competitive exam. But it does leave us asking, are we not bluffing if we are just shooting in the dark? Or maybe it is not bluffing, since everyone including the examiner is aware of this possibility?

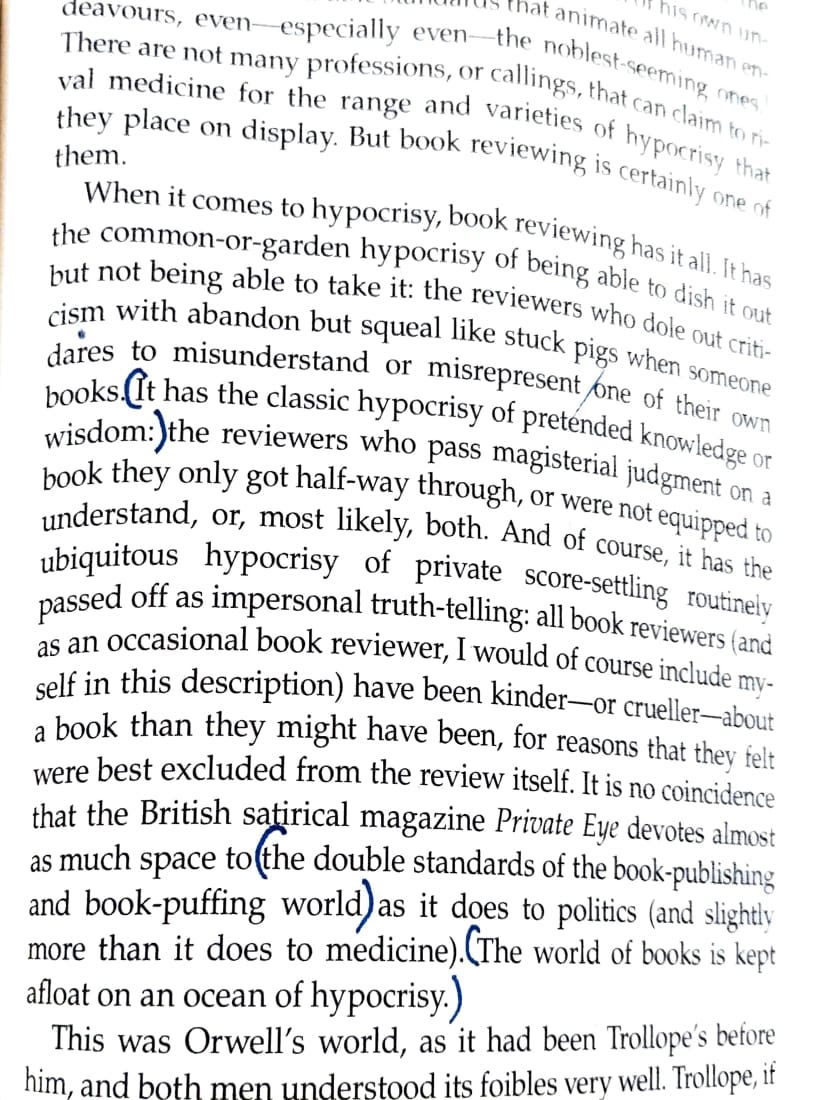

A closely related question here is: don’t we all of us carry around and convey an impression of ourselves to the world? Speaking especially of pretended knowledge expressed in writing, here is an excerpt which talks of George Orwell's argument that book-reviewing is one of the most hypocritical professions.

The above is an excerpt from David Runciman’s 2008 book Political Hypocrisy: The Mask of Power, from Hobbes to Orwell and Beyond.

As pointed out in an earlier One Doubt Please article, here is one question which David Runciman asks in this book:

What kind of hypocrite should voters choose as their next leader? The question seems utterly cynical. But it is actually much more cynical to pretend that politics can ever be completely sincere. The most dangerous form of political hypocrisy is to claim to have a politics without hypocrisy. - David Runciman

Even if this be so, we still need to ask the following questions, in the context of the ethics paper in the civil services examination.

Are the Ethics Paper and the examination system able to counter or penalize candidates’ tendency to adopt practices such as making statements which they themselves do not understand or believe in, in order to make an unduly favourable impression? How does the examination treat candidates who are and are likely to remain morally upright but are not so eager or competent in expressing or “demonstrating” their virtues in writing? How much does the examination system value modesty and an admission of one’s weaknesses? Or does it only or primarily value and reward confidence, even when it is show of confidence, or overconfidence or arrogance?1

As before, the concerns are common to any selection process which aims to make an assessment of ethics and morality. What say?

OK, so we have discussed how and why knowledge may not be enough, and why ethics selection processes may tend to favour appearances over reality and impressions over genuine expressions. Let us now delve upon a third difficulty.

Nothing Like Firsthand Experience

Let me begin by sharing a brief personal experience - a conversation I had with a very senior executive in an organization / company, once upon a good time - don’t ask me when😊. We were discussing a particular work situation. And it so happened that I took the liberty to express my reservations regarding a certain project being executed by the organization the senior executive was heading. I submitted to her that we should not be doing it. She then asked me: what would you have done if you were in my place?

I must say it was very nice and kind of her to ask this question. You know what I replied? I must confess that I am not exactly proud of my reply. From what I remember, I said something like this:

“It would be easy for me to comment on what I would have done if I were in your place. But it is in fact difficult to say, since I may know this only if I actually sit in your place.”

I say I am not exactly proud of this reply, since I think I was driven by an inner instinct to not risk offending the senior executive. I wonder whether I should have simply said: “no, I would not have done it if I were in your place.”

But hey, there is a problem here.

Can I really be sure that I would behave as I now think I want to, if and when I am placed in a situation which I have not yet experienced?

In other words, how much can we rely on the thoughts, beliefs and principles we have today, in order to predict how we will behave in a situation which is at present only in our imagination? In a future which is yet to happen?

Here is a question for you, which can in turn help us answer the above questions.

Have you ever done something which you earlier believed to be absolutely wrong and as something which you would never do?

It is quite disturbing for me to write these words…to admit that I have done some things which I earlier believed I would never do, because I believed it is wrong and dishonourable to do them. I cannot be certain about your case, but I suspect that the same situation holds good for a lot many of us. Or perhaps most of us? Or perhaps, just perhaps, all of us?!?!

We spoke earlier of Morgan Housel’s statement that we do not advertise our weaknesses. It now strikes me that a slightly modified version of this statement would be just as true:

We do not advertise our weaknesses, especially to ourselves.

Because of this tendency, we are likely to be poor judges of our future ethical and moral actions. And also of how we would have behaved if our life experiences and journey had been different. We have reflected on this theme, in the following One Doubt Please article on corruption.

#NotJust "The Corrupt": Are(n't) We All Corrupt?!

Reflections on the eternal malady of corruption; what it means to be corrupt, and how we could hope to combat it

What the above discussion illustrates is a timeless truth which Morgan Housel beautifully captures in his book Same as Ever2.

“Nothing is more persuasive than what you have experienced firsthand…A big theme throughout history is that preferences are fickle, and people have no idea how they will respond to an extreme shift in circumstance until they experience it for themselves.”

In the chapter titled “Now You Get It”, Housel speaks of Varlom Shalamov, a poet who spent fifteen years imprisoned in a Gulag. Here is Housel, quoting Shalamov:

“Take a good, honest, loving person and strip them of basic necessities and you will soon get an unrecognizable monster who will do anything to survive. Under high stress, “a man becomes a beast in three weeks”, Shalamov wrote.”

At the same time, here is what Viktor E. Frankl says in his 1946 book “Man's Search for Meaning”, a memoir based on his experiences in Hitler’s concentration camps during the 2nd World War.

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

So, what do these mean? The point I am trying to make, as Morgan Housel says, is that we do not know until we experience it. At the same time, I believe, and I would like to believe, as Frankl says, that we do have the capability, whatever the circumstances, to choose our attitude.

How do these principles apply to our question of the Ethics Paper of the civil services examination? I think the key is to remember and acknowledge the difference between simulation and real life.

We may do well in an Ethics examination; but does it mean that we will make ethical choices in real life, in the same way we proclaim they should be made, in an examination?

#NotJust The Civil Services Examination

To recap, we have reflected on at least three challenges or questions which add to the difficulty and complexity of evaluating the ethical and moral fibre of civil service candidates, based on an Ethics Paper in the civil services examination.

Does knowledge ensure or predict ethical behaviour? Or is it #NotJust about knowledge?

It is #NotJust appearances or impressions. How well is the examination able to see through the appearances and examine the character underneath the appearances?

Does the examination reflect real-life behaviour? Can it?

And yes, these concerns are not unique to the Ethics Paper. A little reflection will show us that these concerns reverberate through the entire examination system as well.

And #NotJust that of the Civil Services Examination.

I think these concerns are applicable to any mechanism which assesses or seeks to assess or claims it seeks to assess candidates, people - anyone - for their ethical and moral fibre. As such, it is common to all forms of selection - be it any job recruitment, any examination, or even to the question of choosing our life partner (hint: isn’t there generally some difference between courtship period and life after wedding, for instance?😊).

It is difficult. That does not necessarily mean that it does not need to be done.

We need to think of better ways. I have already thought of some ideas in this direction, especially as it applies to the civil services examination. And I hope to be back with them, in another One Doubt Please article.😊

If you have read this far, you would surely be interested to read the following articles as well.

#NotJust The Right Candidate

Reflections on why hiring the right candidates is not enough to improve the integrity of the Indian Civil Services

#NotJust This Time: Why We tend to Keep Slipping If We Fail to Live Our Values Even Once

Reflections on values and principles, and why it is easier to live by our principles 100% of the time rather than 99% of the time

And I am also glad to share with you an article I discovered while I was finishing to write this, which almost quite mirrors my thinking and the observations made here. The article was written in the year 2013, around the time the Ethics Paper was introduced by the UPSC, in the Civil Services Examination. It is titled Testing ethics through an exam, written by Gourav Vallabh, (then) a Professor of Finance at XLRI Jamshedpur.

Fine then, let us close for now. Did you find some value in this article? If yes, please do let me know in the comments section, or at Newdheep@gmail.com. And please also consider sharing this in your social circles, in case you find some value in it. Thank you again!😊🙏

Footnotes

Speaking of the display of confidence, it is interesting to note that this happens at very high levels in all spheres of society.

In their 2023 book, The Big Con: How the Consulting Industry Weakens our Businesses, Infantilizes our Governments and Warps our Economies, Professor Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington argue that the consulting industry is, at least in part, a confidence trick. They say that a consultant’s job is to convince anxious customers that they have the answers, whether or not that’s true.

While the above book is about the consulting industry, a 2019 book by late anthropologist David Graeber titled Bullshit Jobs: The Rise of Pointless Work, and What We Can Do About It (recommended to me by fellow Indian Information Service officer Gautam) takes a dig at this phenomenon of make-believe in an even deeper and broader sense.

If the confidence tricks and the different varieties of pointless work are present in all walks of work and life, as the above authors argue, I would think that it becomes that much more important that candidates entering and staying in the civil services are those who buck the dominant culture. We hope that they should turn out to be and become leaders who can inspire a counterculture - one that is more ethical and moral than the environment and system which they enter.